Google is back in the news for collecting WiFi data. As it turns out, the Europeans are really touchy about Google Street View and their private data. This story started back in 2010, when Google admitted that they were collecting public WiFi information with the same vehicles that drive around the world taking pictures for their Street View and Google Maps applications. Seemed like a good idea, but multiple European privacy agencies got all bent out of shape.

At first, I was sort of on Google’s side on this one. It would cool to have a map of WiFi density. If you read through that blog post from Google, though, you’ll notice that they only meant to collect public information — like the WiFi network name and it’s broadcasting channel — but “mistakingly” collected “samples” of payload data. Huh? I.e. they collected samples of websites that were being visited at unsecured WiFi access points like coffee shops (and if a website had poorly implemented it’s security, they may have collected your personal information, but you can’t really blame Google for that one). That’s creepy. Google claimed they had deleted all the payload data, but Google maintains a worldwide system of redundant storage servers, and it turns out they didn’t get it all deleted.

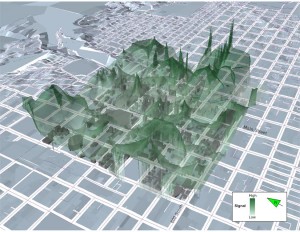

So I’m not on Google’s side anymore. They may be making a good faith effort to make this right, or they may be running a test program to identify which coffee shops slant towards Facebook or Google Plus usage. Such a program wouldn’t be evil, per se, but it would highly unethical. The whole episode brought to mind an article from four years ago where a geographer used basically the same procedure to measure WiFi density in and around Salt Lake City:

Torrens, P. M. 2008. Wi-Fi geographies. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98:59-84.

For those of you without access to academic libraries, you can get a pretty good flavor of his research from this website, and here’s the punchline:

Torrens briefly addressed the issue of private/public space and legalities of collecting his data:

Most computer networks use IP to disassemble and reconstitute data as they are conveyed across networks and routers. Wi-Fi beacon frames essentially advertise the presence of the access point to clients in the surrounding environment and ensure that it is visible (in spectrum space) to many devices. Because they do not actually carry any substantive data from users of the network (their queries to a search engine, for example), it is legal to capture beacon frames. (p. 66)

Two questions: 1) What is the line between the data that is legal to collect and that which is illegal? And are researchers obligated to follow international standards or their home nation’s laws? and 2) Has a human subjects review board ever considered this issue? For example Madison, Wisconsin has a downtown wireless network that sells subscription service. It seems like a valid research question in communications geography to figure out which one of their access points have traffic, during which times of day, the distribution of laptops and smart phones, etc. Could I sample payload data if I just used it to collect presence/absence of users? and cross-my-heart promised to delete the raw data?

Looking around the University of Wisconsin’s IRB website I couldn’t find any memos about collecting ambient wireless signals. And their summary of exempt research might imply that WiFi data collection would be exempt based on its “public” nature, but it’s less clear if it is truly de-identified because Google and Torrens were collecting MAC addresses and SSIDs. True, that’s not like storing a person’s name, but IRB standards generally hold that street addresses are identifying data. The relevant guidelines from the Wisconsin policy on exempt research:

Research involving the collection or study of existing data, documents, records, pathological specimens, or diagnostic specimens, if these sources are publicly available or if the information is recorded by the investigator in such a manner that subjects cannot be identified, directly or through identifiers linked to the subjects.

Hm, I don’t know.